Summary

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (or IPCC) have published a series of reports, which are widely assumed to represent the scientific consensus on man-made global warming.

Since these reports are quite long and tedious, many of the people who have looked at the reports have mostly just considered the “Summary for Policymakers” (“SPM”) sections of the reports. These sections are assumed to accurately summarise the main findings of the entire reports.

In their most recent Summary for Policymakers (September 2013), the IPCC claimed that it is more than 95% likely, i.e., “extremely likely” that “… human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century”. They also claimed that this global warming will become much greater during the 21st century if nothing is done to slow down CO2 emissions.

Because thousands of top climate scientists are involved in the writing of the IPCC reports, these Summary for Policymakers claims are widely assumed to represent the views of all the top climate scientists. However, in this essay, we show that this assumption is a mistake. Those views are certainly expressed by many of the IPCC scientists who are heavily involved in the report writing. But, most IPCC scientists are never even asked for their views on those claims. Indeed, several IPCC scientists are prominent man-made global warming critics who openly disagree with a number of the claims made in the Summary for Policymakers.

The problem is that the IPCC adopt a hierarchical system which gives a relatively small number of scientists the power to dismiss the views of other IPCC contributors, if they disagree with them. So, even though thousands of scientists have some involvement in the writing of the IPCC reports, the final views expressed by the reports are dominated by the views of a few dozen scientists.

Introduction

In the late 1980s, the United Nations (in conjunction with the World Meteorological Organization) set up a panel to review the scientific literature on man-made global warming theory, and assess what the impacts of man-made global warming would be (if it existed). This panel was the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, and they have been charged with writing Assessment Reports of the scientific literature every few years. Their first reports were published in 1990, and their fourth reports were published in 2007. They are currently drafting the fifth set, and an on-line version of the first part of the fifth set (“Working Group 1”) was published in September 2013 – see here. The other two parts are due to be published in 2014/2015.

The IPCC reports are widely perceived to have shown that there is a scientific consensus that man-made global warming from increased CO2 is real, serious, and catastrophic.

When the 5th Assessment Report from Working Group 1 was published in September, the media was littered with articles like the ones shown in Figure 1, reporting on the IPCC claim that it was “extremely likely” (by which they mean more than 95% certain) that the global warming since the 1950s was mostly man-made.

If you are at all interested in man-made global warming, you will probably have heard of this claim (or other similar ones) from the IPCC, even if you haven’t actually heard of the IPCC. This is because most people who discuss climate change in any detail refer to the IPCC reports – either directly from the reports, or else indirectly from other people quoting them. As a result, the IPCC reports are probably the biggest contributor to the current public perception of “the scientific consensus” on man-made global warming. Indeed, Rajendra K. Pachauri, the Chair of the IPCC commented in a January 2010 interview:

I mean, let’s face it, that the whole subject of climate change having become so important is largely driven by the work of the IPCC. If the IPCC wasn’t there, why would anyone be worried about climate change? – Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, Chair of the IPCC, January 2010.

Because hundreds of scientists contribute in some way to each report, and thousands of scientists are involved in the review process, it is not surprising that the reports are generally assumed to represent a solid scientific consensus. However, as we will discuss in this essay, a lot of the opinions expressed by the IPCC contributors are never included (or else are treated in a dismissive manner) in the final reports. This means that the apparent unanimity of views expressed in the reports is a false consensus.

Because the alleged IPCC “consensus” is so widely trusted, many climate scientists who haven’t studied man-made global warming theory or the predictions of the computer models assume that they must be reliable merely “because the IPCC says so”, rather than checking for themselves. IPCC climate scientist, Prof. Judith Curry, has admitted she used to do this, and she is probably not the only one to do so:

In Autumn 2005, I had decided that the responsible thing to do in making public statements on the subject of global warming was to adopt the position of the IPCC. My decision was based on two reasons: 1) the subject was very complex and I had personally investigated a relatively small subset of the topic; 2) I bought into the meme of ‘don’t trust what one scientists says, trust what thousands of IPCC scientists say.’ – Prof. Judith Curry, October 2010.

How the IPCC reports are written

The IPCC like to present their reports as being comprehensive, rigorous reports that are written by a large number of top climate scientists, and carefully reviewed by an even larger number of climate scientists. With this in mind, they often emphasise the large quantities of authors, reviewers, countries, etc. that are involved in the report-writing process.

For instance, Figure 2 shows a screen shot taken from the IPCC’s fact sheet for the Working Group 1 5th Assessment Report. Do you notice all those (literally) large numbers which fill the page? E.g., “209 Lead Authors and 50 Review Editors from 39 countries… Over 600 Contributing Authors from 32 countries… Over 9200 scientific publications cited… 54,677 comments… 1089 Expert Reviewers from 55 countries…”

It certainly sounds impressive. Most of us would naturally assume that any report involving such an extensive array of resources would be both comprehensive and rigorous. However, as we will see in this essay, the discussion of climate science in the IPCC reports is neither comprehensive nor rigorous!

Before we discuss the problems with the IPCC process, it will probably help to briefly describe the structure of the reports and how they are written…

The IPCC is divided into three separate “Working Groups”, and each Working Group is charged with reviewing different aspects of climate change:

- Working Group 1 (WG1) is supposed to assess the physical science basis of climate change

- Working Group 2 (WG2) is supposed to assess the impacts of climate change and the potential for adaptation to reduce the vulnerability to, and risks of climate change

- Working Group 3 (WG3) is supposed to assess the costs and benefits of different approaches to mitigating and avoiding climate change.

Working Group 1 is the only Working Group actually looking at the scientific evidence and explanations for climate change (including man-made global warming). The other two groups explicitly assume that climate change is occurring, is mostly man-made, and will get worse in the future unless CO2 emissions are reduced.

So, since we are discussing the scientific consensus on man-made global warming in this essay, when we are referring to the IPCC reports we will mostly be referring to the Working Group 1 reports, unless otherwise indicated. For shorthand, the three groups are often abbreviated as WG1, WG2 and WG3.

Since the first “Assessment Report” in 1990, there have been several follow-up reports. The most recent complete Assessment Report which has been published is the 4th Assessment Report (2007). But, as mentioned above, the WG1 section of the 5th Assessment Report was published on-line in September, and the WG2 and WG3 sections are due to be published in 2014-15.

Summary of the different Assessment Reports the IPCC have so far published:

| Report | Acronym | Published |

|---|---|---|

| First Assessment Report | FAR | 1990 |

| Supplementary Assessment Report | – | 1992 |

| Second Assessment Report | SAR | 1995 |

| Third Assessment Report | TAR | 2001 |

| 4th Assessment Report | AR4 | 2007 |

| 5th Assessment Report | AR5 | 2013-2015 |

When the second and third Assessment Reports were published, to distinguish between the different reports the acronyms “FAR”, “SAR” and “TAR” were used. However, since “FAR” was already taken by “First Assessment Report”, when they published the Fourth Assessment Report, it was decided to start using acronyms like “AR4”.

Since a lot of literature had already been written referring to the first reports as FAR, SAR and TAR, the IPCC decided to only apply the new naming scheme from AR4 onwards.

Each Assessment Report consists of several (usually quite long) chapters discussing individual topics and a separate “Summary for Policymakers” and “Technical Summary”. For the AR4 WG1 report, there were 11 chapters, while for the most recent AR5 WG1 report, there were 14 chapters.

To write each report, the IPCC select several Lead Authors (LAs), and a couple of Co-ordinating Lead Authors (CLAs) for each chapter. The Lead Authors are then allowed to invite several Contributing Authors (CAs) to “provide additional specific knowledge or expertise in a given area”. Often a Lead Author will invite some of their research assistants or colleagues to be Contributing Authors.

After the initial drafts of all of the chapters have been written, the various Lead Authors look at all of the chapters in the report as a single entity, called the “Zero Order Draft” (or ZOD). Then they suggest modifications that might need to be made to individual chapters, so that each of the chapters tie-in and agree with each other. Once these modifications are made, the draft chapters are compiled together into the “First Order Draft” (or 1OD) and this is sent for review by the Expert Reviewers.

For the first Assessment Reports, the Expert Reviewers were nominated by the IPCC and government bodies. But, recently, the IPCC switched to inviting any interested people to voluntarily register as Expert Reviewers, e.g., see here or here.

At any rate, however they are selected, the Expert Reviewers are allowed to read through the chapters of the First Order Draft, and make comments/corrections/suggestions on the text. The chapter authors then are supposed to take these comments into account, and revise the text.

Once they have done this, a second draft report (“Second Order Draft” or 2OD) is compiled. This is sent to the reviewers, for a second round of review comments. After the chapters have been revised to take into account the second round of review comments, the final draft is published.

In order to ensure the authors adequately account for the review comments when they are revising the text, the IPCC nominate a few Review Editors for each chapter. Often these Review Editors are former IPCC authors.

The above process is carried out for all of the chapters in the Assessment Reports. However, for the Summary for Policymakers, a slightly different process is taken.

The draft text for the Summary for Policymakers is written by a selection of Lead Authors and Contributing Authors, as for the chapters. The authors are supposed to base their draft on the main conclusions and findings in the other chapters. As a result, the authors for the Summary for Policymakers usually consist of authors from the other chapters. But, only a few dozen authors are selected for this process, e.g., for the WG1 AR5 Summary for Policymakers, there were 34 Lead Authors and 37 Contributing Authors.

Importantly, the Expert Reviewers are not allowed to review this text. Instead, the text is reviewed line-by-line by Government Reviewers during a session lasting several days. During this session, delegates from each of the attending governments debate amongst each other any changes that should be made to the text.

The Co-Chairs of the IPCC Working Group, all of the Co-ordinating Lead Authors and the authors of the draft text also take part in the debate – but only in an advisory capacity. The final decisions on any changes are voted on by the Government Reviewers, not the authors. For this reason, in the final report, the Lead Authors and Contributing Authors of the Summary for Policymakers are only described as “Drafting Authors” and “Draft Contributing Authors”.

An account of the changes agreed for the WG1 5AR Summary for Policymakers has been published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Prof. Judith Curry also offers a summary of some of the main changes here.

To get an idea of the types of changes made, let us use the IISD account to consider one aspect of the recent WG1 AR5 Summary for Policymakers – their treatment of the so-called “pause”. At the time of the session, there was a lot of discussion in the media over the growing realisation that global temperatures seemed to have “paused” for the last 10-15 years, even though CO2 emissions had been continuing unabated. For instance here is a BBC interview in July 2013 with UK Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Ed Davey:

This puzzle was a tricky problem for the IPCC panel, because it referred to an apparent contradiction in the data the IPCC had used to reach their main conclusions. Specifically, the global temperature estimates used by the IPCC did suggest that there had been a 10-15 year “pause” in global warming, and the climate models used by the IPCC had not predicted that!

Some climate scientists have been retrospectively trying to come up with possible explanations for this “pause”, e.g., maybe the “missing” heat for the last few years has been going into the deep oceans, and the climate model developers had neglected this possibility… But, the panel probably thought that a lot of people would think this sounded a bit like saying “the dog ate my homework”. So, the panel wanted to come up with a factual way to emphasise the long-term global temperature trends to the public without highlighting the pause of the last 10-15 years.

According to the IISD account, Germany, supported by Belgium and Ireland, suggested singling out the fact that the first decade of the 21st century was the warmest decade since 1850 [at least according to the dataset used by the IPCC, which we criticise elsewhere on this blog]. Alternatively, the IPCC Co-Chairs and Co-ordinating Lead Authors suggested focusing on 30-year time periods, because then the 15-20 years before the pause could be grouped with the 10-15 years of the pause.

In the end, Canada proposed simply adding the word “successively” to one of the sentences in the draft to say: “Each of the last three decades has been successively warmer at the Earth’s surface than any preceding decade since 1850.” This by-passed the problem of the pause, because the pause didn’t start until the late 1990s/early 2000s, and so the 2000s as a whole were still technically warmer than the 1990s! Canada’s suggestion was supported by the Co-ordinating Lead Authors, Slovenia, the US, Austria, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Trinidad and Tobago, and eventually accepted.

One final point to note about the overall format of the IPCC reports is that once the Government Reviewers have made their corrections to the Summary for Policymakers, some of the claims made in the Summary might no longer agree with the actual findings in the chapters! To get around this, the chapter authors are allowed to revise the text in their chapters to better match the Summary for Policymakers, without having to show the revisions to the External Reviewers, if necessary.

In the remaining sections we will look in detail at some of the flaws in the IPCC process, which lead to a false sense of unanimity and consensus amongst the scientific community. But, to summarise the different IPCC roles, here is a short table:

| Title | Acronym | Number involved | Nominated by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-ordinating Lead Author | CLA | 1, 2 or 3 per chapter | IPCC |

| Lead Author | LA | As many as 10-20 per chapter | IPCC |

| Contributing Author | CA | As many as 40-50 per chapter | Lead Authors |

| Expert Reviewer | ER | Hundreds per report | Volunteered |

| Review Editor | RE | 1, 2 or 3 per chapter | IPCC |

| Technical Support Unit | TSU | A few staff for each report | IPCC |

How was this “extremely likely that…” conclusion reached?

Since the IPCC reports are very long and tedious documents, many people rely exclusively on the Summary for Policymakers to accurately summarise the key points discussed of the report. Even climate scientists who might read the chapter(s) relevant to their specialty, will often rely on the Summary for Policymakers to summarise the rest of the report. In addition, the IPCC press releases and all of the media coverage of the Assessment Reports are based almost entirely on the Summary for Policymakers.

As a result, when you hear people referring to the “scientific consensus” on global warming, they are usually referring to the contents of the Summary for Policymakers. Ironically, as we discussed in the previous section, this is the one part of the report which is not subjected to scientific review by the Expert Reviewers. So, the Summary for Policymakers is probably amongst the least scientific parts of the IPCC reports.

In any case, when the 5th Assessment Report of Working Group 1 was published in September 2013, much of the media attention focused on one particular section in the Summary for Policymakers which claimed that it was “extremely likely” that human activity was responsible for most of the global warming since the 1950s. In the 4th Assessment Report (2007), a similar claim had been made, except that at the time, they had made the slightly lesser claim that it was “very likely”. According to the IPCC terminology, “extremely likely” means more than 95% certain, while “very likely” means more than 90% certain. In other words, the IPCC was not only claiming that most of the global warming since the 1950s was man-made – they were implying that the evidence for this claim was even stronger than it had been in 2007.

Not surprisingly, this claim, captured a lot of attention from journalists and bloggers, e.g., here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

With this in mind, in this section, we will:

- Try to figure out the basis for this claim

- Assess if it is a justified claim

- See if it genuinely represents the scientific consensus

First, let us look in detail at the relevant section in the Summary for Policymakers (“SPM”):

Human influence has been detected in warming of the atmosphere and the ocean, in changes in the global water cycle, in reductions in snow and ice, in global mean sea level rise, and in changes in some climate extremes (Figure SPM.6 and Table SPM.1). This evidence for human influence has grown since AR4. It is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century. {10.3–10.6, 10.9} – Section D.3 of the Summary for Policymakers

The numbers in curly brackets “{10.3-10.6, 10.9}” refer to the sections in the IPCC report on which this claim was based, i.e., the claim is based on Sections 10.3-10.6 and 10.9 of Chapter 10. The title of Chapter 10 is “Detection and Attribution of Climate Change: from Global to Regional”.

Indeed, in the Executive Summary for Chapter 10, one of the claims made is “It is extremely likely that human activities caused more than half of the observed increase in global mean surface temperature from 1951-2010.” This is pretty similar to the Summary for Policymakers claim, so it seems likely that the claim was originally made by the Chapter 10 authors.

Interestingly, 17 of the 73 Chapter 10 authors were also draft authors for the Summary for Policymakers. Since there were only 71 draft authors for the Summary for Policymakers, that means that nearly 1/4 of the Summary for Policymakers draft authors (23.9%) were involved in writing Chapter 10. This is quite a large number of authors. So, it seems the contents of Chapter 10 were actually quite influential in drafting the entire Summary for Policymakers.

With that in mind, let us consider what Chapter 10 was reporting. As you might have guessed from its title, there were two aims for Chapter 10:

- The detection of statistically significant changes in climate.

- Attributing those climate changes to different factors.

As you probably know at this stage, the global temperature estimates used by the IPCC suggest that there was a general “global warming” trend over the 20th century. The IPCC global temperature estimates are shown in Figure 4.

However, “detecting” that there has been global warming does not actually tell us what caused the global warming. For instance, maybe it was man-made global warming, or maybe it was natural global warming. Or maybe it was a mixture of both…

This brings us to the other role of the Chapter 10 authors, i.e., “attribution”. They assumed that man-made global warming was real, but recognised that natural global warming could also occur. They wanted to pinpoint at what stage in the 20th century most of the global warming was man-made, as opposed to natural.

All of the current climate models explicitly assume that man-made global warming theory is valid, and that increasing atmospheric CO2 causes global warming. So, one way in which the climate models can simulate “global warming” is by increasing CO2 concentrations.

This means that, in the climate models, global warming is defined as being “man-made” if it is caused by increasing CO2 concentrations.

The current IPCC climate models only include one possible mechanism for natural global warming – changes in solar variability. However, deciding how solar variability has changed since the mid-19th century is tricky, because there are actually quite a lot of different “solar reconstruction” datasets.

Some solar reconstructions suggest that solar activity has been increasing since the 19th century. Others suggest that it increased in the beginning of the 20th century, but then decreased. Yet others suggest that there has been almost no change. See Scafetta, 2011 (Abstract, .pdf available from Scafetta’s homepage) for a review.

When the IPCC climate modellers are carrying out their simulations, they pick one of these solar reconstruction datasets to use. However, so far, they have only used those reconstructions which (a) suggested an early 20th century increase followed by a decrease, or (b) suggested there has been almost no change in solar activity since the 19th century. Surprisingly, none of the IPCC climate models used any of the datasets which suggested that solar activity has been increasing!

More worryingly, many of the models do not include any solar variability! In other words, many of the models include no mechanism for natural global warming. So, it seems that the ability of the climate models to simulate natural global warming is very limited.

Nonetheless, the Chapter 10 authors assume that:

- CO2 causes global warming, and the current climate models accurately describe this.

- The climate models are able to accurately simulate natural climate variability.

- Their global temperature estimates are reasonably accurate, and aren’t seriously biased by urban heat islands, or anything like that.

At this point, we should remind you that we completely disagree with all three of these assumptions! Our “Physics of the Earth’s atmosphere” papers show that CO2 does not cause global warming, and that the current climate models are seriously flawed (summary here). Our “Urbanization Bias” papers show that the global temperature estimates used by the IPCC are strongly biased by urbanization, particularly since the mid-20th century (summary here). But, having said that, the Chapter 10 authors wouldn’t have seen our papers when they were writing their report.

At any rate, by making these assumptions, they decided to take the following approach to answer their question of “when did global warming become mostly man-made?”

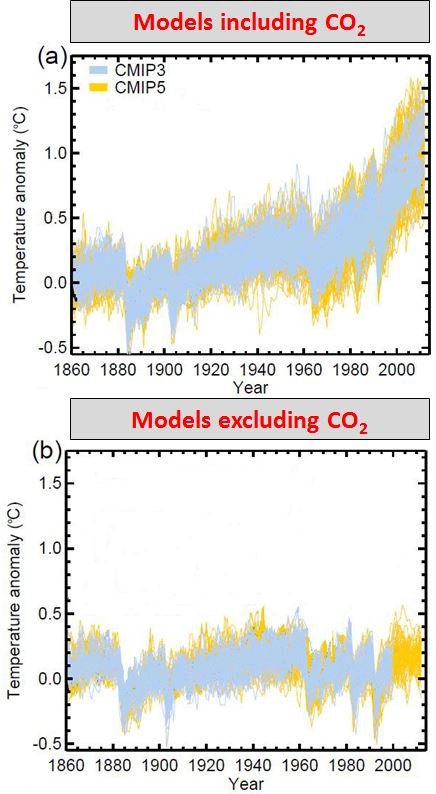

First, they took the global temperature results from one set of climate models which incorporated the known changes in CO2. These are shown in the top panel of Figure 5.

Each of the thin orange lines corresponds to the simulation results from one of the “CMIP5” climate models. These were climate model simulations that were specifically carried out for the 5th Assessment Report. For comparison, each of the light blue lines corresponds to the simulation results from one of the “CMIP3” climate models, which were carried out for the 4th Assessment Report. For more details, the CMIP website is here.

Second, they took a second set of climate model simulations which were identical to the first set, except that CO2 concentrations were kept constant at 19th century levels. These simulation results are shown in the bottom panel of Figure 5.

The simulation results for both sets are fairly similar up to the mid-20th century. However, after then, the models in the top panel show very strong “global warming”, while the models in the bottom panel don’t.

This is not too surprising because (a) CO2 concentrations didn’t actually increase much until about the 1950s, and (b) the current climate models don’t include many mechanisms to account for natural global warming.

At any rate, as we saw earlier, the global temperature estimates that the IPCC use suggest that there was a general global warming over the entire 20th century. So, the Chapter 10 authors concluded that most of the global warming since about the 1950s was “man-made”.

Notice that the Chapter 10 authors were not trying to prove or disprove man-made global warming theory or checking the reliability of the climate models! They were assuming that man-made global warming theory was valid, and that their models were reliable. Instead, they were merely checking at what stage global warming would become “mostly man-made”… if their models were accurate. This is important, because many people mistakenly assume that the authors of the detection/attribution chapters in the IPCC reports were actually testing man-made global warming theory and the climate models.

Note for simplicity, we haven’t mentioned other greenhouse gases and aerosols. In the climate models, increases in greenhouse gases such as methane, and CFCs, are assumed to also cause some global warming, while increases in aerosols are assumed to cause global cooling. In the CMIP simulations, aerosols can either be man-made (e.g., from industrial emissions) or natural (from volcanoes).

So, we now have an explanation for why the IPCC report concluded that “…human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.” But, this leads to another question. Where did the “more than 95% likely” and “extremely likely” bit come from? And why was it only “more than 90% likely” or “very likely” in the 4th Assessment Report? Surprisingly, the origin of these probabilities and likelihoods has not actually been fully explained.

If the authors are definite that most of the global warming since the 1950s is man-made, then they should give a definite and conclusive statement. They either are certain or they aren’t.

Unfortunately, many of the results the IPCC authors describe in the report are actually ambiguous or inconclusive. So, if they are to be true scientists, they cannot make conclusive statements on the basis of those results. This creates a problem for the IPCC organisers.

The IPCC reports are supposed to advise governments on the scientific consensus on climate change. But, governments are rarely satisfied if a scientist says “here, I have some inconclusive results for you!” So, if the IPCC authors don’t make conclusive statements, the reports will not be of much interest to politicians.

After the first few reports, the IPCC decided that they needed a compromise. So, from the Third Assessment Report onwards, the IPCC decided that authors should only make definitive and conclusive-sounding statements, but that they would accompany those statements with an estimate of how likely they felt it was that the statement was correct. That way, the scientists could say “I never said it was conclusive, I only said it was likely”, and the politicians could still say “scientists say so…”

Of course, where one person might say that something was “very likely”, another person might say it was “likely”, and another might say it was only “quite likely”. It’s a very subjective process. To make it less subjective, the IPCC decided to associate a list of specific likelihood terms with statistical probabilities. For instance, the famous “extremely likely” term in IPCC terminology means “more than 95% certain”.

As we will discuss later, assigning these terms is still subjective, but it does mean that the authors can be somewhat consistent in how confident they are when they pick a “likelihood” for their statements.

In the table below, we list the IPCC “likelihood” terminology. For every statement the authors make, they are supposed to pick a “likelihood” from the following scale:

| Scale | Probability | Description in words |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Less than 1% chance | Exceptionally unlikely |

| 2 | Less than 5% chance | Extremely unlikely |

| 3 | Less than 10% chance | Very unlikely |

| 4 | Less than 33% chance | Unlikely |

| 5 | 33%-66% chance | About as likely as not |

| 6 | More than 50% chance | More likely than not |

| 7 | More than 66% chance | Likely |

| 8 | More than 90% chance | Very likely |

| 9 | More than 95% chance | Extremely likely |

| 10 | More than 99% chance | Virtually certain |

It seems that, on a scale of 1 to 10, when the Chapter 10 authors were asked the following question, “how likely do you think it is that most of the global warming since the 1950s is man-made?”, they went with a score of 9 (“extremely likely”). Their predecessors for the 4th Assessment Report went with a score of 8 (“very likely”) and the 3rd Assessment Report authors went with a score of 7 (“likely”).

The above rating scheme hadn’t been introduced for the earlier reports. But, for the 2nd Assessment Report, the authors claimed there was a “discernable human influence on global climate”, which is similar to a score of 6 (“more likely than not”). Meanwhile in the 1st Assessment Report, the authors were unsure whether the reported global warming was due to human activity, or simply due to natural variability, i.e., they felt it was “about as likely as not” to be man-made global warming, which is roughly equivalent to a score of 5.

There seems to be a remarkable pattern:

| Report | Year | Confidence score |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Assessment Report | 1990 | 5 |

| 2nd Assessment Report | 1995 | 6 |

| 3rd Assessment Report | 2001 | 7 |

| 4th Assessment Report | 2007 | 8 |

| 5th Assessment Report | 2013 | 9 |

It looks like with each report the IPCC authors simply increase their confidence score by 1! If that’s all that they’re doing, does that mean that if there is a 6th Assessment Report, they will increase their confidence score to 10 (“virtually certain”)? If so, what will they do if there is a 7th Assessment Report? Will they add more scores to the scale so that they can increase their confidence “up to eleven” or will they instead start decreasing their confidence?

At any rate, whether this stepwise increasing up the scale by one with each report is a coincidence or not, it is actually very surprising that they chose to increase their confidence at all for the 5th Assessment Report.

For the 4th Assessment Report, their attribution studies only looked at the 20th century, specifically, 1900-1999. However, as we mentioned in the previous section, in the last 10-15 years, global temperatures seem to have “paused”, even though CO2 emissions have continued to rise.

This means that the attribution studies for the 4th Assessment Report stopped just at the time “the pause” was starting. As a result, the apparent match between the models and data was actually better for the 4th Assessment Report period, than it is now!

For this reason, a few months before the WG1 5th Assessment Report was published, IPCC author, Prof. Hans von Storch, voiced his concern that “the pause” suggested to him that the climate models are much less reliable than had been assumed at the time of the 4th Assessment Report, and that the scientific community should be openly re-evaluating the models:

So far, no one has been able to provide a compelling answer to why climate change seems to be taking a break. We’re facing a puzzle. Recent CO2 emissions have actually risen even more steeply than we feared. As a result, according to most climate models, we should have seen temperatures rise by around 0.25 degrees Celsius (0.45 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 10 years. That hasn’t happened. In fact, the increase over the last 15 years was just 0.06 degrees Celsius (0.11 degrees Fahrenheit) — a value very close to zero. This is a serious scientific problem that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) will have to confront when it presents its next Assessment Report late next year. – Prof. Hans von Storch, interview with der Spiegel, June 2013

Prof. Judith Curry (another IPCC author) also believes that the failure of the climate models to predict the “pause” in global warming indicates that the IPCC has substantially underestimated the role of natural variability in recent climate change, e.g., see here, here, here or here.

If the “pause” is causing climate scientists to question the reliability of the climate models, then this should have led the IPCC authors to reduce their confidence in their claim that most of the global warming since the 1950s was man-made. But, instead the Chapter 10 authors actually increased their confidence from 8 (“very likely”) to 9 (“extremely likely”)!

Most readers would probably assume that this was a well documented, scientifically determined decision, and that it arose from rigorous debate amongst the scientific community. However, remarkably, the decision was a confidential one made by the Chapter 10 (and perhaps Summary for Policymakers) authors, and we, along with the rest of the scientific community, do not actually know for certain exactly why they chose “more than 95% certain”.

Indeed, this was one of the criticisms of the IPCC made by a 2010 InterAcademy Council committee to review the IPCC process:

… it is unclear whose judgments are reflected in the ratings that appear in the Fourth Assessment Report or how the judgments were determined. How exactly a consensus was reached regarding subjective probability distributions needs to be documented. – Committee to review the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, InterAcademy Council, October 2010 – p39

As we mentioned earlier, the claim of “extremely likely” confidence was mentioned in both the Summary for Policymakers and Chapter 10. With this in mind, it seems likely that those 17 authors who were involved in the writing of both Chapter 10 and the Summary for Policymakers to us were predominantly responsible for the decision.

So, we suspect that it was at least one of the following 17 IPCC authors who actually made the claim:

| Author | Chapter 10 role | Summary for Policymakers role |

|---|---|---|

| Nathaniel L. Bindoff | Co-ordinating Lead Author | Drafting Author |

| Peter Stott | Co-ordinating Lead Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Myles Allen | Lead Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Nathan Gillett | Lead Author | Drafting Author |

| Gabriele Hegerl | Lead Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Judith Perlwitz | Lead Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Olivier Boucher | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Jonathan Gregory | Contributing Author | Drafting Author |

| Georg Kaser | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Reto Knutti | Contributing Author | Drafting Author |

| Valerie Masson-Delmotte | Contributing Author | Drafting Author |

| Gerald Meehl | Contributing Author | Drafting Author |

| Viviane Vasconcellos de Menezes | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Timothy Osborn | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Joeri Rogeli | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

| Drew Shindell | Contributing Author | Drafting Author |

| Peter Thorne | Contributing Author | Draft Contributing Author |

Still, whoever ultimately made the decision, and whatever their reasons, we can definitely state that it does not represent an actual consensus amongst the scientific community. For instance, as we mentioned above, Profs. von Storch and Curry have both independently said that the “pause” should have led to a decrease in confidence.

On her blog, Curry has summarised her own understanding of the origin of the “95%” figure. Curry has never been involved in the writing of the Summary for Policymakers. Nonetheless, she is an IPCC scientist, and contributed to one of the chapters in the 2001 Working Group 1 report. The following text is taken from a blog post she wrote just after the WG1 5th Assessment Report Summary for Policymakers was published (see here):

“Yesterday, a reporter asked me how the IPCC came up with the 95% number. Here is the exchange that I had with him:

Reporter: I’m hoping you can answer a question about the upcoming IPCC report. When the report states that scientists are “95 percent certain” that human activities are largely to cause for global warming, what does that mean? How is 95 percent calculated? What is the basis for it? And if the certainty rate has risen from 90 in 2007 to 95 percent now, does that mean that the likelihood of something is greater? Or that scientists are just more certain? And is there a difference?

JC: The 95% is basically expert judgment, it is a negotiated figure among the authors. The increase from 90-95% means that they are more certain. How they can justify this is beyond me.

Reporter: You mean they sit around and say, “How certain are you?” ”Oh, I feel about 95 percent certain. Michael over there at Penn State feels a little more certain. And Judy at Georgia Tech feels a little less. So, yeah, overall I’d say we’re about 95 percent certain.” Please tell me it’s more rigorous than that.

JC: Well I wasn’t in the room, but last report they said 90%, and perhaps they felt it was appropriate or politic that they show progress and up it to 95%.

Reporter: So it really is as subjective as that?

JC: As far as I know, this is what goes on. All this has never been documented.”

If even IPCC scientists like Prof. Curry don’t know how or why the IPCC decided on this 95% claim, then it doesn’t seem like much of a “scientific consensus”. Yet, this seems to have been one of the most widely quoted claims of the IPCC report!

How rigorous is the review process?

Since the first IPCC reports were published, there have been complaints from some of the Expert Reviewers that they had strongly disagreed with specific claims being made in the report, but their review comments seemed to have been completely ignored.

For instance, Dr. Patrick J. Michaels who was a contributing author to the 1995 IPCC report was also a reviewer for the same report. However, even though he had several serious criticisms of the draft report, and gave quite detailed reviews explaining his concerns, nothing was done in the final report to address these concerns:

Several of my review comments, especially on Chapter 6 in the June review, speak directly to problems in the climate models. My comments consist of 4,639 words and resulted in not one discernable change in the text of the IPCC drafts.

– Dr. Patrick J. Michaels, hearing before the U.S. House of Representatives, November 16, 1995 (link here)

For the first IPCC reports, the reviewer comments and the chapter author responses were confidential, and never revealed to the public. So, the public was unable to assess how rigorous the IPCC review process was, and how valid the complaints of reviewers like Michaels were.

However, for the 4th Assessment Reports, the IPCC finally agreed to release the comments. You can browse through the archive of all the review comments and the responses for Working Group 1 in an archive maintained by the Harvard College Library. Review comments and responses for Working Group 2 and Working Group 3 are available on the IPCC websites.

The review comments/responses for the latest WG1 5th Assessment Report haven’t been published yet. But, we can get some insight into the review process by analysing the 4th Assessment Report comments.

John McLean (an IT professional from Melbourne, Australia) has carried out an analysis of the Second Order Draft review comments for the Working Group 1 report. He is very cynical of the IPCC, but nonetheless, his report is quite informative, and is worth reading (download here).

According to McLean’s report, a total of 308 reviewers commented on the Second Order Draft. But, nearly half of the reviewers only commented on one chapter, and there were only five reviewers who commented on all the chapters. Quite a few of the reviewers only made one comment on a chapter, and only about half of the reviewers made more than 5 comments on a chapter. This suggests that the popular impression that the IPCC reports are subject to intensive review by thousands of Expert Reviewers is inaccurate.

But, the process becomes even less impressive when we realise that more than 30% of the Expert Reviewers commenting on the Second Order Draft were actually IPCC authors who had also registered as reviewers – 95 out of the 308 reviewers were IPCC authors. This is worrying – if the IPCC reports accurately represent the views of the IPCC authors, then why did so many of the authors feel the need to comment as Expert Reviewers?

But, what about those independent reviewers who did comment on the drafts? Were their comments taken on-board?

Dr. Vincent Gray (a retired chemist, and critic of man-made global warming theory) has been an expert reviewer for the IPCC since the 1992 report. In fact, it turns out that he single-handedly submitted 16% of all the comments analysed in McLean’s report! But, despite strongly criticising man-made global warming theory in his review comments, he finds most of his comments are simply ignored:

As a Reviewer for the IPCC right from the 1992 Supplement to the first Report I have submitted a very large number of comments on their drafts. For all of the Reports up to the fourth I had no way of finding out whether any of my comments had been accepted except by comparing the wording of the Final Report with my comments… The publication of all of the comments on the Second Draft of the WGI Report of the Fourth Report in Harvard University (2009) was the first time I had ever seen the replies to my comments on any Report. I submitted 1,878 comments. 16% of the total, most of which were rejected without answering them. – Dr. Vincent Gray, “Spinning the climate”, May 20, 2013

Steve McIntyre was another Expert Reviewer who made a large number of detailed criticisms on the Working Group 1 report, specifically on the paleoclimate chapter (Chapter 6). However, again, most of his comments were either dismissed out-of-hand by the chapter authors. In some cases, the authors agreed that his comments were valid, and said that they would revise the text. But, when McIntyre looked at the “revised” text of the next draft, no actual changes had been made! See here or here.

See here or here for similar examples from other reviewers.

These problems were not just confined to Working Group 1. In the chapter on glaciers in the 2007 Working Group 2 report, the chapter authors had claimed that there was a very high chance the Himalayan glaciers would melt away by 2035. However, a few years later during a scandal which had quite a bit of media coverage, e.g., here or here, the IPCC admitted that the authors had had no scientific basis for making this claim.

Defenders of the IPCC pointed out that this was only “…a single error, on one page of one volume of a mammoth three-volume report” (Robin McKie, The Guardian blog, 24th January 2010). However, it turns out that two separate Expert Reviewers had actually spotted and pointed out the error during the Second Order Draft, but the chapter authors had done nothing to fix the error! See p22 of the InterAcademy Council’s 2010 review of the IPCC, for a more detailed discussion.

Dr. Richard Tol, who is himself an IPCC author, found similar problems for Working Group 3. He believes the IPCC process is fundamentally flawed. In particular, he has warned of “… the inability of the IPCC to constructively engage with valid criticism” (see here).

After Tol studied the final version of Working Group 3’s 4th Assessment Report he found a large number of what he regards as serious mistakes and errors. Perhaps other researchers might disagree with him on some of these points. However, the fact that he is an IPCC author, yet still considers the IPCC report to be inaccurate and error-ridden, indicates that – at the very least, the reports don’t accurately describe the range of views of the IPCC authors, i.e., they don’t reflect the actual scientific consensus.

More worryingly, when Tol looked at the reviewer comments and the responses, he found that the errors and mistakes that he identified had already been pointed out by reviewers during the review process, but had made it into the final report nonetheless. He concludes that:

In sum, the review process of the IPCC failed miserably. [The 4th Assessment Report of Working Group 3] substantially and knowingly misrepresents the state of the art in our understanding of the costs of emission reduction. It leads the reader to the conclusion that emission reduction is much cheaper and easier than it will be in real life. – Dr. Richard Tol, March 2010

Obviously, with a controversial and complex subject like climate science, there are bound to be disagreements between different scientists. So, it is likely that in some cases, the chapter authors genuinely believe that the reviewers who disagree with them are “wrong”. And, in many cases, they may well be.

But, if the IPCC reports are meant to be taken as the “scientific consensus” on climate change, then the authors have an obligation to indicate aspects in which controversy exists. Dismissing the review comments of the expert reviewers just because the chapter authors are convinced that they are right and the reviewers are wrong is not good enough.

Another problem with the review process is that the Expert Reviewers are often not given access to the data the chapter authors used for reaching their conclusions.

For instance, when Dr. Patrick Michaels (who we mentioned earlier) was carrying out his reviews for the 1995 report, he asked the IPCC in five separate inquiries for access to a key dataset that had been used in the report (output data from a particular climate model), but was refused. He warned the IPCC staff that he “… was being refused data absolutely critical to a proper peer review of [the IPCC report]“ (hearing before the U.S. House of Representatives, November 16, 1995), but was still not given the data.

Steve McIntyre, mentioned above, also was refused access to data important for assessing some key statements in the paleoclimate chapter of the 2007 report. He was even threatened with being fired as a reviewer if he persisted in his requests – see here.

If the Expert Reviewers are not allowed access to the data that the chapter authors are relying on for specific claims, then this can severely limit the reviewers’ ability to assess the claims of the authors. As a result, the review process is much less rigorous than it should be.

What about the Review Editors? According to the IPCC guidelines, Review Editors are supposed to “…assist the Working Group/Task Force Bureaux in identifying reviewers for the expert review process, ensure that all substantive expert and government review comments are afforded appropriate consideration, advise lead authors on how to handle contentious/controversial issues and ensure genuine controversies are reflected adequately in the text of the Report.”

Each chapter has 1, 2 or even 3 Review Editors. So, maybe they might make sure that the chapter authors adequately respond to the review comments, and ensure that the various controversies in the field are accurately described…

Unfortunately, it seems that many of the Review Editor comments amount to little more than a “rubber stamp” approval.

In 2008, David Holland managed to obtain (through Freedom Of Information requests) all of the Review Editor comments for the 4th Assessment Reports of Working Groups 1 and 2 – see here.

For 38 out of the 43 Review Editor chapter reports for Working Group 2, their entire reports essentially consisted of a filled-in form letter like the one shown in Figure 7.

For the Working Group 1 Review Editors, the situation was similar. 25 of the 26 Review Editor chapter reports simply contained the following 25 word sentence:

I can confirm that all substantive expert and government review comments have been afforded appropriate consideration by the writing team in accordance with IPCC procedures.

The only Working Group 1 Review Editor who submitted a longer report was Prof. John Mitchell. But, even his report was only a two paragraph long letter (156 words) – see here. Not believing that this was the entire extent of the Review Editors’ contributions, David Holland wrote to John Mitchell, to double check there weren’t some more detailed comments that the IPCC hadn’t given him. Mitchell replied that Holland wasn’t missing anything, and that the two paragraph letter was his complete report:

I can confirm that you have had the complete Review Editors report and that there was no supplemental information submitted with the Review Editors report. I hope this answers your enquiry. – Prof. John Mitchell responding to David Holland, February 20, 2008

It seems that, even though the Review Editors nominally had the power to ensure that the chapter authors were more rigorous in their treatment of the review comments, in practice, they generally chose not to.

How representative are the papers cited by the IPCC?

One of the main selling points of the IPCC reports is that they reference thousands of scientific publications. Until recently, the IPCC claimed that they only used scientific publications which had been peer-reviewed. However, in 2010, a Canadian journalist and author, Donna Laframboise, arranged an audit to check how many of them were actually peer-reviewed, and found that only about 2/3 of them were – see here for a summary of her findings.

She describes these findings and some of her other criticisms of the IPCC reports in this 4 minute interview on 30th October 2011:

Perhaps because of Laframboise’s audit, the claim that all of the cited papers are “peer reviewed” is no longer made. Instead, the IPCC now make the lesser claim that “(p)riority is given to peer-reviewed literature if available” (Working Group 1 Fact Sheet).

Nonetheless, whether peer-reviewed or not, it is true that the reports reference thousands of papers. For the more recent Working Group 1 reports, each chapter on its own typically cites several hundred papers.

This might create the impression that each chapter represents a comprehensive review of the literature for each topic. However, this is misleading. In the last few decades, climate science has become a very popular subject with thousands of new papers being published each month. As a result, for every paper cited by the chapter authors, there are often dozens of other relevant papers they are not citing.

The chapter authors are only supposed to reference a few hundred papers for the entire chapter. This means that they might only discuss a few dozen papers for each subtopic, even if there are hundreds (or thousands) of important papers published on that subtopic. Deciding which of these papers to mention can be quite a subjective process, and other experts on a subtopic might strongly disagree with the selection made by the IPCC authors.

In this light, it is worrying how many of the references cited in the chapters are papers written or co-authored by the chapter authors themselves.

We analysed the references cited in Chapter 3 of the Working Group 1 2007 report and compared the authors of each of the papers to the IPCC authors involved in writing Chapter 3. Out of the 803 papers referenced in the chapter, 309 of them (38.5%) were co-authored by at least one of the chapter authors. Often the papers were co-authored by more than one of the chapter authors.

John McLean has also analysed the references cited in Chapter 9 here. He found that 213 of the 534 papers referenced (39.9%) were co-authored by at least one of the chapter authors. This is similar to our findings for Chapter 3, which suggests that this high percentage of self-citations is pretty typical.

Essentially, the chapter authors were reviewing their own work…

Now, on the one hand, this is understandable. If the IPCC selected their authors correctly, then the authors for each chapter should be amongst the top scientists working on the topics being discussed in the chapter, i.e., they will have written a lot of the papers published on the topic.

Still, it puts the Lead Authors into an awkward position. They are being asked to summarise the literature on a topic in which they presumably feel they are experts. It would be very easy for them to describe the papers they consider “right” favourably, and to be dismissive of (or even ignore!) the papers they consider to be “wrong”.

Former IPCC Lead Author, Dr. John Christy, described the problem in a March 2011 US Government committee hearing (available here – interested readers might want to watch the video webcast of the testimony at this link. Dr. Christy’s testimony begins at about 31 minutes.):

In essence, the [IPCC Lead Authors] have virtually total control over the material and, …, behave in ways that can prevent full disclosure of the information that contradicts their own pet findings and which has serious implications for policy in the sections they author. While the [Lead Authors] must solicit input for several contributors and respond to reviewer comments, they truly have the final say.

In preparing the IPCC text, [Lead Authors] sit in judgment of material of which they themselves are likely to be a major player. Thus they are in the position to write the text that judges their own work as well as the work of their critics. In typical situations, this would be called a conflict of interest. Thus [Lead Authors], being human, are tempted to cite their own work heavily and neglect or belittle contradictory evidence

In fact, because the IPCC reports are so highly-regarded by the scientific community, this has a self-perpetuating effect. The papers cited favourably in one IPCC report will be viewed more positively by the scientific community than the ones cited dismissively (or not even cited). This means that, for the next report, the scientists who have been promoting the “right” view are even more likely to be considered positively, and may even be asked to be an IPCC author.

Additionally, when the authors are reviewing the literature, they are supposed to only refer to papers which have been published before a specific deadline, decided by the IPCC staff. By the time the final draft is being written, new papers might have been published which the authors feel are relevant, but were published too late for the original deadline. For this reason, the IPCC staff slightly alter the deadline rules to allow some papers to be referred to by the authors.

This might seem reasonable, except that most of the papers for which these rules are altered are ones that agree with the authors’ views, rather than being included to provide a more up-to-date discussion of the literature, e.g., see here. In the case of one paper (Wahl & Ammann, 2007 – Abstract; Google Scholar access), the IPCC staff allowed the chapter authors to refer to it, even though the paper had not even been accepted for publication by the official IPCC deadline! See here for a detailed summary of exactly why the Wahl & Ammann, 2007 paper was so important to the authors of Chapter 6 of the WG1 4th Assessment Report.

Case study of IPCC literature review: discussion of the urban heat island debate

As an example of how one-sided the chapter authors could be in their reviews, let us consider the discussion of urbanization bias, since this is a topic which we have written a series of three papers on (summary here).

At the time the AR4 was being written, there were a lot of studies in the peer reviewed literature which suggested that urban heat island effects had introduced a strong warming bias into the global temperature estimates.

But, there had also been a few papers which claimed that this urbanization bias was negligible. See our “Urbanization bias I. Is it a negligible problem for global temperature estimates?” paper (Summary here), for a detailed review and discussion of the debate.

Obviously, it was important to have some discussion of the urban heat island problem in the chapter dealing with the global temperature estimates – Chapter 3. So, the chapter authors included a very brief section discussing urban heat islands. The Lead Author in charge of this section was David Parker and the Co-ordinating Lead Authors in charge of the chapter were Prof. Phil Jones and Dr. Kevin Trenberth.

David Parker and Prof. Phil Jones were coincidentally co-authors of five of the papers that claimed urbanization bias was negligible – Wigley & Jones, 1988 (Abstract); Jones et al., 1990 (Abstract; Google Scholar access); Easterling et al., 1997 (Abstract; Google Scholar access); Parker, 2004 (Abstract; Google Scholar access); and Parker, 2006 (Open access). Also, Dr. Kevin Trenberth had written a comment (Trenberth, 2004 – abstract; Google Scholar access) criticising the Kalnay & Cai, 2003 study (Abstract; Google Scholar access) which suggested that nearly half of the apparent warming trends in the U.S. were probably due to urbanization bias (or land use changes).

Clearly, the chapter authors had very strong views on the urbanization bias debate. This wouldn’t be a problem if they acknowledged that other scientists held differing views, and that the topic was the subject of considerable debate and controversy. However, they didn’t do this…

In fact, if you read the relevant section in the chapter (Section 3.2.2.2 Urban heat islands and land use effects), you could be forgiven for believing that the entire debate had been completely resolved, and that the urban heat island problem was nothing to worry about!

There was plenty of very favourable discussion of the papers which claimed that urbanization bias was negligible. But, there was almost no discussion of the studies which suggested that urbanization bias was substantial.

The top panel shows the ‘global warming’ trends of several of the global temperature estimates, and the bottom panel shows the global increase in urban population. Taken from our Urbanization Bias I paper. Click on image to enlarge.

The chapter authors did mention that the Kalnay & Cai, 2003 paper (mentioned above) had concluded that urbanization bias was a serious problem (along with land use changes).

But, the chapter authors then immediately proceeded to dismiss the study, by implying that it was unreliable, and citing three papers that criticised Kalnay & Cai, 2003 – including Trenberth’s one.

Remarkably, they made no reference to Kalnay & Cai’s response to their critics – Cai & Kalnay, 2004 (Abstract; pdfs of Cai & Kalnay’s reply can be found in the pdfs for Trenberth, 2004).

Cai & Kalnay, 2004 was actually on the following page of the same journal issue of two of the articles the chapter authors cited. So, it is very odd that the chapter authors didn’t mention it. Neither did they mention any of Kalnay et al.’s follow-up papers, such as Cai & Kalnay, 2005 (Open access). It seems their summary of the debate around the Kalnay & Cai study was incomplete and very one-sided.

In the First and Second Order Drafts of the chapter, the authors seemed happy to leave the discussion at that. But, after strong criticism from some of the External Reviewers, they reluctantly decided to mention two other papers – McKitrick & Michaels, 2004 (Open access) and de Laat & Maurellis, 2006 (Open access).

Both of these papers found that urbanization and related industrial activity had strongly biased global temperature estimates. And unlike the controversial Kalnay & Cai, 2003 paper, neither of them had been criticised in the peer reviewed literature.

As we mentioned earlier, one of the claims of the IPCC at the time was that the IPCC reports were supposed to be only summarising the peer-reviewed literature, and not doing their own research. So, by rights, when the authors referred to these papers, they should have at least balanced the discussion in their previous drafts by acknowledging that there was on-going debate. They didn’t do this.

Instead, the authors decided to come up with their own non-peer reviewed reasons to dismiss the paper, in 3 sentences, without referring to any peer-reviewed papers! They never even e-mailed McKitrick, Michaels, de Laat or Maurellis to ask them if they wanted to respond to this 3-sentence criticism. They seem to have just decided that they were “right”, and that the McKitrick & Michaels and de Laat & Maurellis could therefore be dismissed without any further discussion.

Dr. A. Jos de Laat later tried to publish an article defending his work, although he couldn’t it get it published. The unpublished draft is available on his website, and is worth reading if you’re interested in his side of the story.

See here for a discussion of the chapter authors’ initial attempts to ignore the McKitrick & Michaels, 2004 and de Laat & Maurellis, 2006 papers, and their final decision to dismiss them without providing any references.

Having ignored or dismissed any papers which disagreed with their views, the authors then stated categorically in the chapter’s Executive Summary that “Urban heat island effects are real but local, and have not biased the large-scale trends.”. This claim was then repeated in the Summary for Policymakers, and thereby became part of the “scientific consensus”:

Urban heat island effects are real but local, and have a negligible influence (less than 0.006°C per decade over land and zero over the oceans) on these values. – IPCC WG1 AR4 Summary for Policymakers

We appreciate that Parker, Jones and Trenberth might have personally believed this to be the case. But, as we discuss in our “Urbanization Bias” papers, there were (and still are!) many scientists who disagree with that – including us.

Rather than accurately describing the long and on-going debate which genuinely existed over the urbanization bias problem, the chapter authors ignored or dismissed the papers they personally disagreed with and presented the papers they agreed with (and in some cases had co-authored!) as definitive. In effect, they created a “consensus” on urbanization bias which coincided with their own views.

Do the IPCC scientists actually agree with the IPCC reports?

Certainly there are a number of IPCC authors who are convinced that the Summary for Policymakers claims accurately represent the scientific consensus.

For instance, Dr. Richard Somerville has claimed that:

[Scientists] have established that the climate is indeed warming and that human activities are the main cause – Somerville & Hassol, 2011 (Google Scholar access, DOI access)

Similarly, Dr. Brian Soden has claimed that:

If you look at the increase in global mean temperature over the last fifty years, the vast majority of that is associated with human activity and the burning of fossil fuels. – Dr. Brian Soden,January 2010

Dr. John Houghton, the chairman of the IPCC Working Group 1 for their first three Assessment Reports, and the founder of the UK Met. Office’s Hadley Centre (an organization which was set up in 1990, after the publication of the first IPCC reports, specifically to predict the impacts of man-made global warming, rather than to test whether it existed or not) has written that:

As a climate scientist who has worked on this issue for several decades, first as head of the Met Office, and then as co-chair of scientific assessment for the UN intergovernmental panel on climate change, the impacts of global warming are such that I have no hesitation in describing it as a “weapon of mass destruction”. -Dr. John Houghton, The Guardian, 28th July 2003.

But, on the other hand, there are IPCC authors who strongly disagree with the claims in the Summary for Policymakers

For instance, Prof. John Christy (who we mentioned earlier) believes that most of the climate change in recent decades is natural in origin, and that the man-made global warming predicted by the climate models is unrealistic. Here is a 13 minute radio interview with him from April 2011 (unfortunately the sound quality is a little noisy):

Similarly, Dr. Hugh W. Ellsaesser in a letter to the Environmental Science & Technology journal, July 1991 stated that:

…I am one of the stronger supporters of the proposition that the available records indicate climate warming over the past century or so. It’s just that I don’t believe the observed warming is due to an increase in greenhouse gases.

Dr. Patrick J. Michaels (mentioned earlier) and Dr. Robert Balling, Jr. have both been very vocal in explaining that they believe there might be some man-made global warming, but that most of the climate change since the Industrial Revolution is probably naturally-occurring. They argue that the current climate models are unreliable, and that the apocalyptic predictions of the models are completely unfounded. See for example, their 2009 book, Climate of extremes: Global warming science they don’t want you to know.

These views don’t match with the claims associated with the IPCC report. Yet, both Michaels and Balling are IPCC scientists, and have contributed to the IPCC reports.

Another IPCC contributor, Prof. George Kukla, has said that:

The only thing to worry about [global warming] is the damage that can be done by worrying. Why are some scientists worried? Perhaps because they feel that to stop worrying may mean to stop being paid. – Prof. George Kukla in an e-mail interview with Mari Krueger for Gelf magazine, April 2007

Prof. Richard Lindzen has predicted that:

Future generations will wonder in bemused amazement that the early 21st century’s developed world went into hysterical panic over a globally averaged temperature increase of a few tenths of a degree and, on the basis of gross exaggerations of highly exaggerated computer predictions combined into implausible chains of inference, proceeded to contemplate a rollback of the industrial age.

Dr. Roy Spencer argues that:

The IPCC is totally obsessed with external forcing, that is, energy imbalances imposed upon the climate system that are NOT the result of the natural, internal workings of the system.

Below is a clip of him in a 2008 testimony to a US senate committee:

Even amongst those IPCC scientists who believe that man-made global warming is a serious concern, there are many who believe that the relative role of man-made global warming have been overestimated, and that the role of natural climate variability has been underestimated

For instance, Prof. Judith Curry (mentioned earlier) has made it quite clear that she disagrees with several of the claims implied by the IPCC:

Why is my own reasoning about the implications of the pause, in terms of attribution of the late 20th century warming and implications for future warming, so different from the conclusions drawn by the IPCC? […]

my reasoning is weighted heavily in favor of observational evidence and understanding of natural internal variability of the climate system, whereas the IPCC’s reasoning is weighted heavily in favor of climate model simulations and external forcing of climate change. – Prof. Judith Curry, 20th September, 2013

All of the scientists quoted above have contributed to at least one IPCC report, and so are part of the “thousands of experts” involved in writing the reports. But, they clearly disagree with the so-called “scientific consensus”. In other words, the IPCC reports do not represent the full range of views of the IPCC contributors, let alone the rest of the scientific community.

Conclusions

IPCC scientist, Prof. Mike Hulme commented on his website in 2010 that:

The IPCC consensus does not mean – clearly cannot possibly mean – that every scientist involved in the IPCC process agrees with every single statement in the IPCC! Some scientists involved in the IPCC did not agree with the IPCC’s projections of future sea-level. Giving the impression that the IPCC consensus means everyone agrees with everyone else – as I think some well-meaning but uninformed commentaries do (or have a tendency to do) – is unhelpful; it doesn’t reflect the uncertain, exploratory and sometimes contested nature of scientific knowledge.

We would agree with this.

Prof. Hulme himself believes that there is at least some man-made global warming, and in the 1990s was a major advocate of urgent action (see here for his summary of the evolution of his thoughts on “climate change”). But, as he argues in his thoughtful book, “Why we disagree about climate change“, there are actually a wide range of different views on climate change (man-made and natural), and it is foolish to try and simplify these views into a one-size-fits-all “scientific consensus”.

The claims made by the Summary for Policymakers are clearly believed by many scientists. But, we shouldn’t mistakenly think that because a certain view is expressed in the IPCC reports, it is also believed by the “thousands of scientists” who were involved in the writing of the IPCC reports. In this essay we gave several examples of IPCC reviewers and IPCC authors who disagree strongly with many of the claims made in the IPCC reports.

If there are IPCC authors and reviewers that strongly disagree with the claims being made in the IPCC reports, then the claims are by definition not unanimous, as is often implied. The apparent unanimity of the conclusions in the IPCC reports is an artificial construct.

Instead, it seems that, for each topic in the reports, the most influential authors within the IPCC heirarchy decide what they think the “scientific consensus” should be. Once they have made their decision, any dissenting views from the rest of the IPCC authors are then dismissed as being “minority views”…

That does not seem to us a reliable way for finding out what the actual scientific consensus on man-made global warming is. To paraphrase the singer Shania Twain, the IPCC doesn’t impress us much:

So what do the main differences appear to be between this report and the last one?

[…] shown in the right half of SCC15 Figure 8. For a more complete critique of Bindoff, et al. see here (especially section […]